As if in a flash of summer lightning,

Apple trees, a river, the bend of a road.

And it should contain more than images.

Singsong lured it into being,

Melody, a daydream. Defenseless,

It was bypassed by the dry sharp world.

You often ask yourself why you feel shame

Whenever you look through a book of poems

As if the author, for reasons unclear to you,

Addressed the worst side of your nature,

Pushing thought aside, cheating thought.

Poetry, seasoned with satire, clowning,

Jokes, still knows how to please.

Then its excellence is much admired.

But serious combat, where life is at stake,

Is fought in prose. It was not always so.

And our regret has remained unconfessed.

Novels and essays serve but will not last.

One clear stanza can take more weight

Than a whole wagon of elaborate prose.

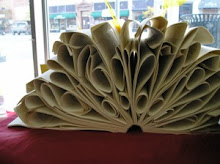

I came to p oetry relatively late, at least consciously. Reading The Odyssey, “Rime of the Ancient Mariner”, and “Ode to a Grecian Urn” for Jean Steele in high school did not at first appear to crack the surface of my indifference. Years passed before I, for no apparent reason, pulled a book of poems by a Polish poet from the shelf in a university book shop. Now at least half of what I read is poetry.

oetry relatively late, at least consciously. Reading The Odyssey, “Rime of the Ancient Mariner”, and “Ode to a Grecian Urn” for Jean Steele in high school did not at first appear to crack the surface of my indifference. Years passed before I, for no apparent reason, pulled a book of poems by a Polish poet from the shelf in a university book shop. Now at least half of what I read is poetry.

My tastes are quite specific. I look to poets who address those battles where life is at stake—they are out there. As such, Europe’s poetic tradition calls to me, most specifically, those East Central European poets for whom History matters.

Others look for the wit of Wilde, Nash, and Parker; or to the macabre of Poe; or the succinct rhythms of Dickinson; the genius of Whitman. The genre is wide; the tragedy is that poetry is a tough sell in this country. I attended a poetry reading in 1992 by Czeslaw Milosz, winner of the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1980. I doubt that more than a hundred people attended, yet that night remains one of the highlights of my life. The power of words, words read aloud, as poetry is meant to be, resonated throughout that hall.

Beginning with the great epics of Homerus, poetry has an illustrious pedigree. Dante gave us an unforgettable tour of Hell. Through Shakespeare’s pen the beauty and power of the English language achieved it pinnacle. In Poland, the poets were the bards that kept alive the idea of a dismembered nation. Akhmatova gave voice to those stricken mute by the terror of Stalin.

I had the great fortune to have a friend—Lorraine Sizer—for whom poetry still mattered. We bonded over Whitman fifteen years ago. In her last years, afflicted by Parkinson’s Disease, I rarely saw her, but she would call me at the shop. We would talk of everything, but poetry was, to the last, what gave our friendship a depth unimaginable without it. She was able to recite verse from memory, encompassing works from a wide variety of poets from all over the world. I read her my favorite poets, she recited from hers. She died last year. Whenever I read Loren Eisley, Edna St Vincent Millay, or John Masefield, I think of her.

The torch of Whitman is flickering. One does not have to be an insatiable consumer of poetry. It is, as Robert Gray wrote in Shelf Awareness, perfectly acceptable to be a casual reader of poetry. One just needs to recognize that certain ideas, specific emotions, the power of words, can only be expressed fully in verse. Anyone who has read a prose translation of The Odyssey understands the loss.

April has been tagged with the monomer of National Poetry Month, but as Goethe suggested, one ought each day to read a good poem…….